Editor’s Note

As of 2023, babiri.net has been rebranded to Statsugiri. To find out more, read here.

Prologue

After 2 months and 132 commits, babiri V2’s API has been launched! babiri is comprised of an API for aggregated usage stats gathered from Pokémon Showdown replays. I’m particularly excited to share how babiri came to be, why it exists, and the technology powering the project. This post is also inspired by Kevin’s zeal.gg write-up, which is a fantastic read on another competitive gaming tool.

A Children’s Game

In 2005, I received a copy of Pokémon Emerald for the Nintendo Game Boy. This would be my gateway to the Pokémon franchise, as I’d end up sinking countless hours into the series of games. I have fond memories challenging the Battle Frontier, capturing Shadow Lugia at Citadark Isle, hunting secret base flags in The Underground, and many more through the years. However, it wasn’t until high school I discovered the Pokémon competitive scene.

In the summer after my first year at UBC, I had the privilege of representing Canada at the Pokémon World Championships. Prior to this, I had mostly attended local tournaments for the past 3 years. I decided to travel out of Canada for the 2016 season to make a bid for a Worlds invite. Through my efforts, I managed to place Top 16 at Oregon Regionals, Top 4 at Seattle Regionals, and 1st at a stacked Midseason Showdown to secure my Worlds invite and a travel stipend to Nationals. Though I had mediocre placings at Nationals and Worlds, it was an unforgettable experience living out my childhood dreams for a year.

babiri V1

At the beginning of 2020, I wrote babiri V1 to help players gain insight on usage stats for the competitive scene. Though I wasn’t actively competing in Pokémon any longer, I sensed there was potential in bringing data-driven analytics to the competitive scene. Being a former competitor also meant I could conveniently generate my own user stories. There was precedence for tools aimed at competitive players with sites such as Pikalytics and VGCStats. What started as a single Python script writing to a CSV file became a tool with quite the following; the site garnering 100k visitors in its first few months and was even featured on the Pokésports Podcast. Though the community was quite happy with babiri, it’s been long overdue for a rewrite as tech debt and tight coupling have made it difficult to add new features.

Following my last internship and graduation, I had 2 months without any commitments, which was the perfect time to tackle the rewrite. Though the end product is simple, there were some interesting abstractions and design decisions in babiri’s backend and data pipeline. At the time of writing, I have indefinitely put the frontend on hold due to work commitments. However, I intend to deploy a fully functioning site at some point in the future.

Teambuilding as a Problem

To compete in a Pokémon tournament, one must build a Pokémon team first. Aaron Traylor, a top competitor and PhD student, eloquently explains the complexity found within competitive Pokémon teambuilding.

This game is unique among zero-sum strategy games for several reasons, but mainly because of its emphasis on the “draft” phase: both players select their action space within the game, and afterwards make actions in the environment. The draft phase is common in other games that AI systems have successfully played (League of Legends, DotA 2, Honor of Kings), but in Pokémon, the draft phase is scaled up to an astronomically large state space (roughly 10^200), meaning the game will require novel research before an AI can achieve superhuman strength.

Teambuilding is arguably the most complex aspect of Pokémon. A team is comprised of 6 individual Pokémon. Each Pokémon has an item slot and 4 moveslots. Furthermore, there are different EV spreads (ie. builds) in how a Pokémon is trained. For instance, Thundurus functions very differently with an offensive build compared to a defensive build. Many players likely agree a robust team should maximize its number of positive (ie. winning) matchups while minimizing weak matchups. Since no team is perfect, it becomes a trade-off balancing which matchups are strongly positive and which matchups are worth compromising.

Data-Driven Pokémon

It is common for competitive players to spend months refining a team through multiple iterations. During the 2016 season, my friends and I piloted the same archetype for 5 months up until Nationals. Great teams have effective answers to common metagame fixtures; for instance, players may have opted to build teams with a positive matchup against the popular Groudon / Xerneas archetype in 2016, as one would’ve expected this team to frequently appear at tournaments. Metagame trends shift as players improve their teams and innovate new ideas throughout the season.

Observing top-performing teams provides valuable insight into metagame trends. One of the leading platforms for ranked games is Pokémon Showdown, an open-source battle simulator. Pokémon Showdown allows players to rapidly build teams and practice against other players online. The site also features a ranked ladder system and replay sharing capabilities. A common preparation tactic involves players reviewing public replays of high ranked users. It is reasonable to assume high ELO-rated users are piloting robust and performant teams to achieve top ladder results. Furthermore, players may modify their teams to better handle performant metagame threats. At its core, the project started with automating the process of searching for teams from replay logs of top ranked ladder users. Even just parsing the 6 Pokémon on each team everyday would provide a wealth of data to work with.

There were few tools focused on Pokémon Showdown data, such as Pikalytics offering monthly reports of usage stats from Smogon servers. However, there was a niche in offering granular team data on a daily basis, especially since querying individual public replays manually was time-consuming and monotonous. Ultimately, the end goal was to build a robust system which would extract team information from replay logs given a format. Insights such as time-series individual Pokémon usage and team archetypes trends would be accessible all in one place and anyone could leverage the public API for their own research purposes (eg. ML, data visualization, etc).

Rewrite Objectives

There were a few notable objectives I aimed to hit for the backend and data pipeline rewrite.

- Open-Source: It was exciting seeing interest in open-source contributions following the first release. Making it open-source would help other developers make similar tools, as I’ve also received many questions on how I implemented certain features. It also provides an element of transparency, as babiri does not support botting to scout for private team replays. Indirectly, making the project open-source holds me accountable to write good code.

- Tests: I’ve come to appreciate well-written tests since the first iteration. Though not the most exciting part of development, tests are crucial in saving developers from massive headaches when pushing new features.

- CI/CD: Continuous Integration / Continuous Development is especially valuable with more than one developer on the project. Automating tests and formatting helps ensure linted and functioning code is merged. Github Actions was fairly straightforward for setting up a workflow for the project.

- Additional Formats: Given the vast number of available formats, it was important to consider an easy way to provision adding or removing formats from the data pipeline and server.

Tech Stack

The rewrite featured a few changes focused on infrastructurte, but retained the majority of the V1 stack.

Golang

The backend server was implemented in Go with Mux as the framework of choice. Having learned it for CPEN431 last year, Go’s familiarity was an asset for timely development and surprisingly pleasant to work with. babiri V1’s backend was written in JavaScript (JS) since the web development tutorials I relied upon were heavily catered to JS. Another consideration was writing the backend in Python with a framework such as Flask or Django. However, both JS and Python lack static typing checks as interpreted languages; I strongly prefer languages where the compiler throws concise error messages so I can produce robust code. The fast compile times, static typing system, and simple deployment (ie. go build) solved most of the issues I encountered when working with non-trivially sized Python codebases. However, I faced a few issues with documentation for certain libraries and working with generics would’ve been appreciated. Both of these can be attributed to Go being a newer language, though the latter is being addressed in the upcoming Go 1.18 release. Nonetheless, Go has made itself a favourite of mine for backend development.

Python

Python was used extensively for the data pipeline due to its familiarity. Beyond being my comfort language, Python was used in both versions of the data pipeline for its fantastic data scraping capabilities. In particular, the requests and beautifulsoup4 libraries combined with regex greatly simplified data parsing. Python also features great tooling support, such as with black for formatting and mypy for static type checking.

MongoDB

Choosing a NoSQL database provided flexible schemas, allowing for rapid changes during the development process. Mongo Atlas, MongoDB’s cloud service, made hosting and connecting to instances a breeze. Initial consideration was made for DynamoDB, but MongoDB’s free tier was sufficient for the project. The only issue I encountered was MongoDB’s free tier blocked certain operations (eg. $in), which meant rewriting certain queries to use available operations.

AWS Lambda

AWS Lambda was the perfect tool for deploying the data pipeline. Previously, the data pipeline was hosted on an EC2 instance but I was dissatisfied with the resources consumed as it was only needed once every 24 hours. Leveraging AWS Lambda’s “pay as you run” model made it cost-effective and scalable. Lambda supporting Docker images through Elastic Container Registry also helped streamline deployment.

AWS EC2

I opted to host the server on an EC2 instance due to Go’s ease of deployment. The deployment process is handled with Docker building the binary and spinning up a container. Due to my inexperience with the AWS Lambda / API Gateway stack, I was overly cautious of potential skyrocketing costs with hosting a public API. Fewer things (eg. my wallet) were likely to go wrong with an EC2 deployment. Nginx sits at the front of the EC2 instance to provide port forwarding and SSL encryption for the server.

Data Pipeline

Module Architecture

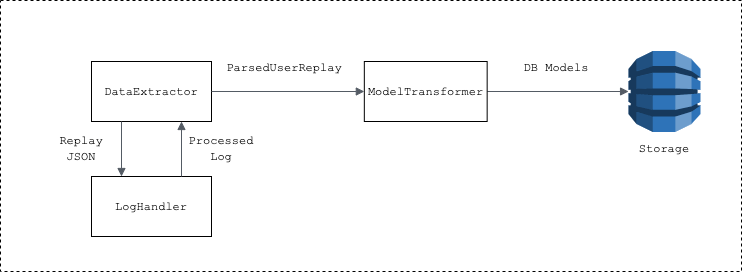

The data pipeline is comprised of 3 main modules: DataExtractor, LogHandler, and ModelTransformer. It is named after Drilbur, the mole Pokémon. Below is a diagram representing data flow between modules.

The DataExtractor ingests, parses, and extracts replay data. The Lambda handler passes the format to run as an argument. The log retrieval process is as follows:

- Retrieve the users from the Pokémon Showdown ranked ladder for the specified format.

- Iterate through the users retrieved. Given a user, find all available replay logs.

- Given the list of replay logs, find the most recent for the specified format and pass it to the

LogHandler. If no replays for the format are found, skip to the next user.

An uncommonly known tip is one can access a replay’s data by appending .json. For instance, https://replay.pokemonshowdown.com/gen8vgc2020-1197324298 would become https://replay.pokemonshowdown.com/gen8vgc2020-1197324298.json. The log is also directly accessible by appending .log instead.

The LogHandler processes logs into an internal ParsedUserReplay model. Upon feed being called, the logs are sanitized to make regex parsing easier (eg. accounting for alternate-form Pokémon in team preview). Below is an example of an unsanitized and sanitized log:

|poke|p1|Dragapult, L50, F|

|poke|p1|Zacian-*, L50|

|poke|p1|Torkoal, L50, F|

|poke|p1|Charizard, L50, F|

|poke|p1|Indeedee-F, L50, F|

|poke|p1|Whimsicott, L50, M|

|poke|p2|Pyukumuku, L50, M|

|poke|p2|Sneasel, L50, F|

|poke|p2|Urshifu-*, L50, F|

|poke|p2|Lapras, L50, F|

|poke|p2|Toxapex, L50, F|

|poke|p2|Eternatus, L50|

--------------------------

|poke|p1|Dragapult|

|poke|p1|Zacian|

|poke|p1|Torkoal|

|poke|p1|Charizard|

|poke|p1|Indeedee-F|

|poke|p1|Whimsicott|

|poke|p2|Pyukumuku|

|poke|p2|Sneasel|

|poke|p2|Urshifu|

|poke|p2|Lapras|

|poke|p2|Toxapex|

|poke|p2|Eternatus|

From the sanitized log, regex parses the replays to populate the ParsedUserReplay, which acts as the internal state shared with ModelTransformer. The abstraction makes adding future new properties (eg. items) easier. The ModelTransformer finally converts the fields from ParsedUserReplay to the database models.

Infrastructure

The DataExtractor is deployed as a private AWS Lambda function. To trigger a run everyday, the Lambda function is connected to a scheduled EventBridge event with a cron expression. The EventBridge event sends a payload following the format of {"format": [FORMAT]}. For every format supported, an EventBridge trigger is required.

As previously mentioned, ECR is used to easily deploy Docker images to AWS Lambda. Although it is currently manually configured, I may explore integrating the process into CI using AWS Actions.

Server

The server connects to the MongoDB Atlas instance through the official MongoDB Go driver, which utilizes bson to make remote procedure calls in MongoDB. Each route creates queries by constructing an aggregation pipeline representation of type []bson.M using a pipeline utility function. Stages may be added to the pipeline if certain parameters (eg. filtering by pokemon) are passed via the request. The route passes the pipeline to a query wrapper function, which abstracts the queries from the application logic. Upon returning results, the transformer layer populates the response after pagination is applied.

Deployment

As previously mentioned, the server is deployed on an EC2 instance using a Dockerfile to build the binary. Amazon Route 53 is responsible for DNS resolution to the babiri.net domain using an EC2 elastic IP. Nginx provides port forwarding to bypass potential privileged port (ie. 80/443) issues and TLS encryption through Nginx and Let’s Encrypt via Certbot for automatic certificate renewal.

Caching

In an effort to reduce network calls, I implemented an in-memory caching service for related /teams endpoints, as they often serve the most traffic. I initially considered caching with Redis, but opted to write my own to save time and hosting efforts. The cache is a key-value dictionary which maps a unique composite key to a team snapshot response, where the composite key is a string comprised of the operation type and appended with query parameters if provided. A separate goroutine monitors the cache entry’s lifetime based on the write time. When an entry’s lifetime exceeds the set time-to-live (TTL), the entry is removed from the cache to be eventually collected by the garbage collector. I leveraged dependency injection to deterministically test the time-based cache eviction policy.

An interesting point about Go’s garbage collection (GC) is related to why Discord switched from Go to Rust a few years ago. Their caching did not meet performance expectations due to latency spikes from Go forcing GC every 2 minutes. Latency spikes did not improve even after the Discord team tuned SetGCPercent. I’ve also experienced similar issues first-hand, when many of my classmates and I ran into performance problems stemming from Go’s GC for our CPEN431 project. Fortunately, this is not a concern at babiri’s current scale and performance requirements. Should any issues arise, the cache could be removed entirely with few consequences. Alternatively, I wouldn’t mind trying my hand at Rust given enough free time.

An additional benefit to caching is lower request latency due to bypassing database access. Though comprehensive benchmark tests were not conducted, local testing produced latency reduction by over a factor of 40,000 (specifically, the benchmark was 48.31 ms to 1.17 μs). That being said, implementing such a simple cache for solely latency reduction is not recommended as the difference is negligible in real-time.

Conclusion

For how ambitious the timeline and scope was, I am quite happy with the final product. It was especially satisfying to have my coursework, internships, and design team experience culminate into a personal project. After being involved with Pokémon for so many years, working on babiri has been a great way to contribute back to the competitive scene. There’s still much work to be done, but I look forward to presenting a finished product to the community. I hope to see more developers, statisticians, and anyone else working on competitive game tooling in the future.

Special Thanks

Though development was a sole effort, a few individuals helped me through the process.

- Leslie Cheng: for providing fantastic development advice, design review, and AWS infrastructure guidance.

- Tony Chen: for providing design review and almost convincing me writing a cache wasn’t worth it.

- Pikalytics: for always being willing to bounce ideas and leading exciting development in the field.

If you have any questions or suggestions pertaining to the project, feel free to message me on Twitter!